Every tourist destination aspires to achieve an eternal commemoration as a “World Heritage” destination. The momentous designation by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) has been administered since 1978. For the past 54 years, it has been handed to 1,157 sites, both natural and man-made structures, spread across 167 countries.

ASEAN boasts itself as one of the regions with the most extensive collection of these incredible heritages. It is home to 41 extraordinary places spanning over nine countries. Indonesia holds the most at nine, followed by Vietnam with eight and the Philippines and Thailand with six locations each. Trailing behind are Malaysia and its four wondrous spots, Cambodia and Laos each with three sites, Myanmar with two, and one from Singapore with its beautiful Botanic Gardens.

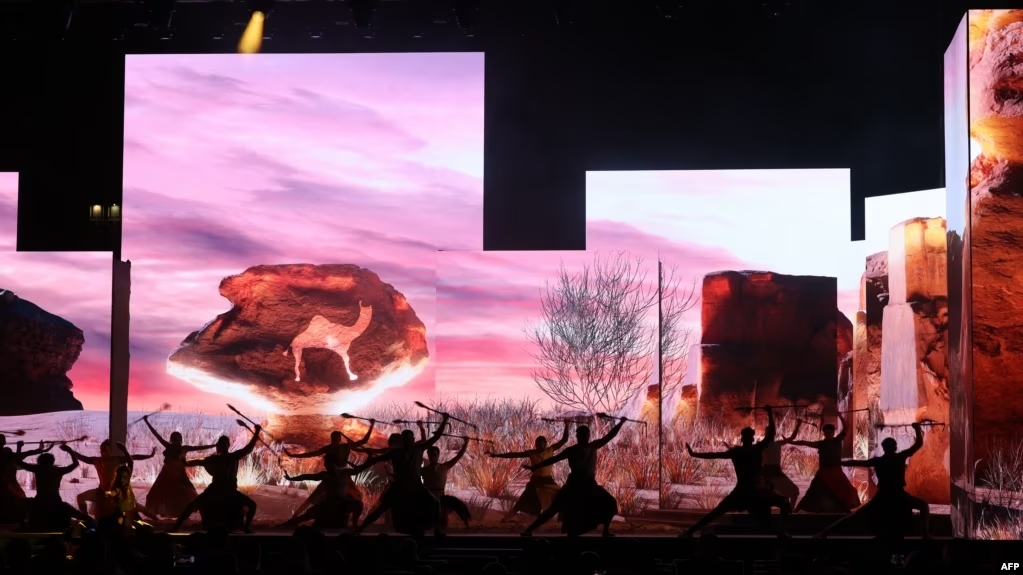

With the 45th Session of the World Heritage Committee currently taking place in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia from September 10 to 25, let’s proceed with our discussion of the most recent designated sites across Southeast Asian nations.

Lenggong Valley, known as a rare breeding ground for early humans spanning from the Paleolithic period to the late Iron Age (depending on which account), encapsulates nearly a million years of human history. Situated in the Perlak State of West Malaysia, this magnificent site was enshrined as a World Heritage site in 2012. The area is littered with seven sites — three cave-like and one open-air ground covering a core area of almost 400 hectares.

The earliest artifacts to have ever been found in the valley were located in Cluster I of the Bukit Bunuh site. It was a human-made stone tool-like item with an estimated age of 1.8 million years and a workshop of stone crafting about 74,000 years old. The three caves, excavated in 1997, were presumed to have been temporary dwellings of local groups some 13 millennia ago. A famous bone structure resembling a human skeleton, referred to as “Perak Man,” was unearthed inside the Gunung Runtuh cave. It was estimated to have been buried for 11,000 years before being discovered in 1991.

Aside from the extensive archaeological sites, Lenggong is renowned for its Geopark, which features various natural wonders, including the meteorite crater resulting from Indonesia’s ancient Mt. Toba eruption, Lata Kekabu Forest Reserve, the Chenderoh Lake, and the lively Perak River.

Lenggong has just been designated as Malaysia’s second geopark in 2021 with a subsequent nomination to be named as a Global Geopark by late 2023. These measures were taken as part of a marketing campaign to energize the area as an ecotourism destination, in addition to the potential archaeo-tourism development following the World Heritage designation.

The Ministry of Tourism, Arts and Culture of Malaysia has agreed to hand over the management of Lenggong Valley to the local state government of Perak. The minister hoped that the management would be more thorough, emphasizing direct oversight by the relevant authorities in their day-to-day operations, with the aim of enhancing Perak’s overall tourism industry..

It is important, however, to educate the Lenggong local communities and empower them on the preservation of the site as well as making innovative approaches to attract tourists. A World Heritage Site designation usually brings economic benefits to surrounding local people due to the increased attention it garners. Such a phenomenon is also observed in Lenggong, yet strong guidance from local authorities is needed to balance basic necessities like sufficient food and protect fragile sites from the threat of over-tourism.

Myanmar’s Glimmering Stupas in the Sacred Landscape of Bagan

Although Myanmar currently has only two World Heritage Sites to its name, it surely feels proud to have Bagan as part of its cultural heritage. The eight compounds of Bagan are the direct result of the merit-making teachings of Theravada Buddhism that take the idea of giving and philanthropy to a whole new level.

Erected by the King of Bagan Kingdom, these temples were constructed amidst a glorious period of luxury and economic prosperity between the 11th and 13th centuries. With no less than 3,595 recorded monuments, Bagan hosts invaluable pieces of Buddhist architecture, scripts, frescoes, and relics. Furthermore, the complex sitting on the bend of the Ayeyarwady River is also an active pilgrimage site that contributes much to the development of Myanmar’s tourism industry.

Inscribed in the honored list in 2019, Bagan has been a prima donna among Myanmar’s domestic and international visitors. Sadly, due to the hostile military takeover of the civilian government in 2021, Bagan saw a rapid decrease in travel-goers and pilgrims as security became an issue too lethal to be neglected. The bloody coup has wreaked havoc on the country, with estimated extrajudicial killings of thousands and with thousands more held in custody.

Recent UN reports found that the country may well be in the lead-up to a civil war. This bitter reality was exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic unexpectedly shattering Bagan and its regional economic activity. Consequently, the World Heritage Site saw no tourists for the past 2.5 years, with local communities hastily abandoning the shining pagoda areas in search of peace and safety.

The adjacent heritage site of Pyu Ancient City has also been bombarded with military fortresses and barbed wires, effectively blocking outside aid from reaching the local communities of Hanlin where the ground is located. The regime intentionally guards themselves within the premises of these sites to deter resistance groups from rebelling against them.

Calls from both local and international advocacies demand UNESCO to list Pyu Ancient City and Bagan as endangered so that more aid and focus could be directed toward the preservation of these priceless jewels. Bagan may have slowly regained its visitors. However, all of them are of domestic origin with no foreigners in sight.

The military regime has made efforts to revive the nation’s economy by partnering with Thai military-owned media corporations to promote Bagan. This includes targeting Thai tourists, who represent the largest inbound tourist group.. Yet, with many incidents of temple torching and village burning done by the Myanmar regime, it would be hard to appeal to international tourists to flock back to Bagan. Locals are hopeful that the illustriousness of Bagan and its reminiscence of the old Burmese Empire could bring the two warring parties of Myanmar back together to rebuild the nation.

The Philippines’ Scenic Wildlife Sanctuary at Hamiguitan Mountain Range

If you go to this mountain ridge that spans north-south along the Pujada Peninsula in the Southeastern past of the Philippines, there you will find an abundance of exotic terrestrial and aquatic flora and fauna which are endemic to Mount Hamiguitan. Among these are the endangered tree Shorea polysperma, the iconic Philippine Eagle (Pithecophaga jefferyi), and the enchanting Philippine Cockatoo (Cacatua haematuropygia). Out of the 1,380 species living in this natural habitat, 341 of them are endemic to the Philippines, with 75% of all amphibians and 84% of all reptiles found only in this forest.

Enshrined as one of the Philippines’ three natural World Heritage Sites in 2014, the area also contains the largest bonsai field forest as well as a natural science museum. This also makes it one of the few World Heritage Sites that is also an ASEAN heritage park.

Mount Hamiguitan is also famous as a hiking trail, which begins at the town of San Isidro. Only 30 hikers are allowed to access the camping ground in order to preserve the pristine environment. Mount Hamiguitan Wildlife Sanctuary is located within the Great Province of Davao Oriental and is managed by an independent board called The Mount Hamiguitan Protected Area Management Board (PAMB) under the Philippines’ National Integrated Protected Areas System (NIPAS).

Although a five-year tourism management plan is currently being implemented to develop the area sustainably, the forest ground is being threatened by a slew of large-scale mining operations. Governor of Davao, Corazon Malanyaon, assured that she would try to cancel the implementation approved by the Philippines Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR) to avoid further ecological destruction.

As with other World Heritage Sites, precious places like these are prone to multi-dimensional threats such as mismanagement due to lack of local awareness, environmental destruction spurred by illegal mining, and even existential damage caused by unstable politics as seen in Bagan.

UNESCO tirelessly warns nations to not mix politics with culture and to put more effort into protecting the longevity of these irreplaceable pieces of world history. All stakeholders must commit to strong collaboration by both the public and private sectors as well as the residents surrounding the sites to help preserve the integrity of the sites while ensuring that their beauty could still be enjoyed by generations to come.

About the Author

Muhammad Rayhansyah Jasin

Rayhan aspires to be an academic journalist and he is trying to start this journey by becoming APU Times’ Head of Journalist Department and a writer in AYO Post. As an IR student at Ritsumeikan Asia Pacific University, he really likes to debate and write other people’s perspectives in his preposition to bridge differing minds. He’s a hands-on traveler who appreciates history and urban-people culture more than nature-based adventures.